Fort and Family: The peacetime occupants of Fort Columbia

When we picture an active military fort, we think of soldiers running drills, gun batteries firing, inspections and loading mines into the river. All of those were normal, everyday aspects of life at a Columbia River fort. However, that only tells one side of the story of life at these forts. The other side of the story looks past wartime and focuses on peacetime, when families of soldiers stationed at the fort could come live alongside them.

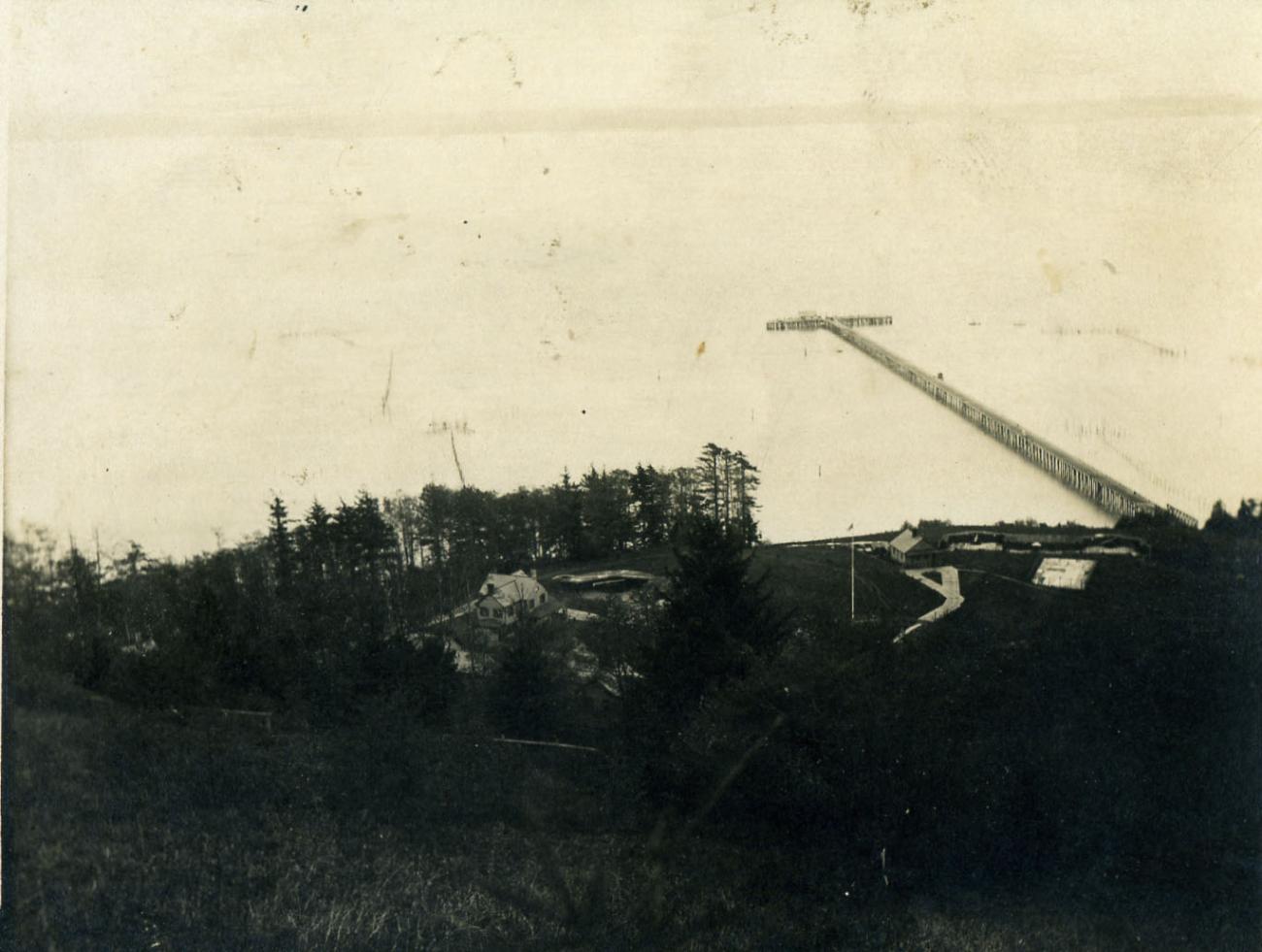

Sitting on the rolling, green 850-foot-high Scarborough Hill, Fort Columbia overlooks the mighty Columbia River. Today, hikers tackling the trails at Fort Columbia can take in some breathtaking views, but historically, soldiers valued the fort not for its scenery, but for its strategic location that allowed gun batteries and surveillance to easily spot potential enemies in the river.

This lookout view is why Congress pushed for Fort Columbia’s construction in 1896, during the Endicott era when many of the United States' coastal defenses were getting upgraded.

Life Before World War One

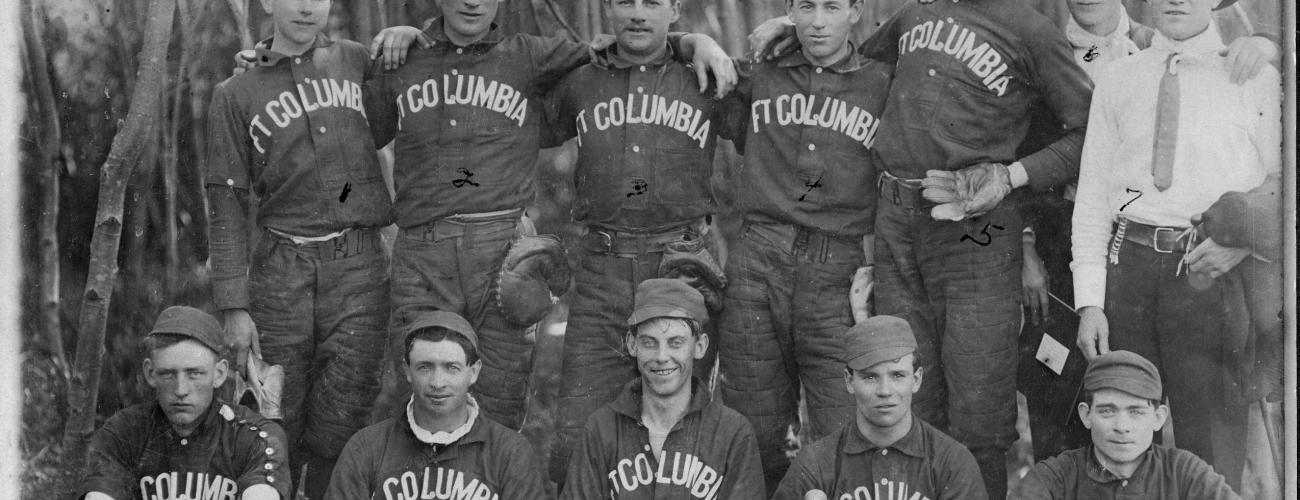

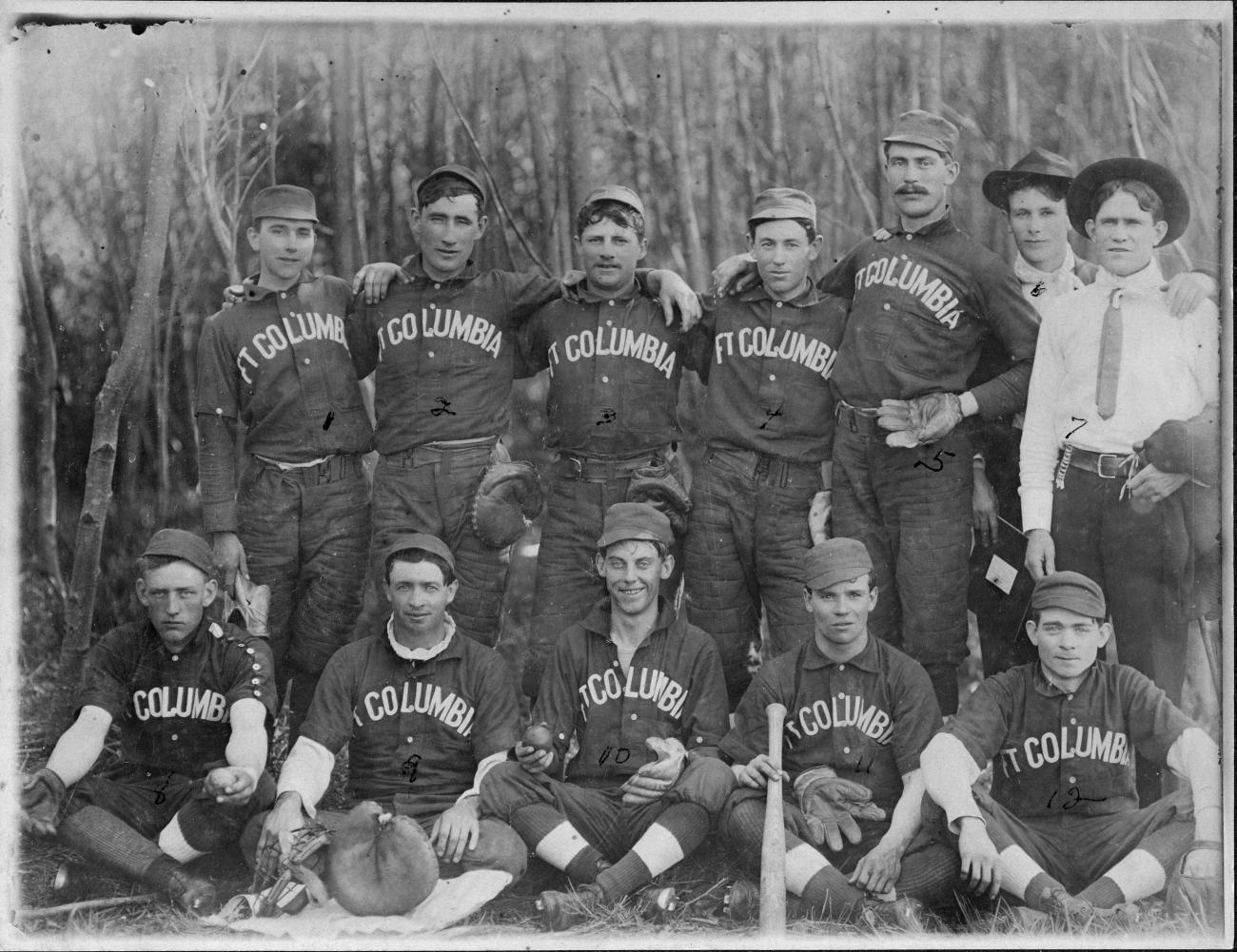

Fort Columbia was officially commissioned for service and fully garrisoned on July 1, 1903. Life at the Fort was relatively peaceful during this time. A typical day for a soldier stationed at Fort Columbia involved keeping up with construction and landscaping, target practice using the gun batteries, inspection, classes on anything from first aid to small arms and free time playing baseball, hosting parties and endless games of cards.

Unlike enlisted men who spent their nights in the Barracks, officers at Fort Columbia had separate housing. At night, these men would return to their families who were living at fort with them. One of those officers was Colonel Frederick W. Phisterer, who commanded Fort Columbia from 1905-1909. He lived in the Commanding Officer’s quarters alongside his wife, Jessie and their daughter, Isabel, who was born in the house in 1907.

As commanding officer of Fort Columbia, Col. Phisterer oversaw a multitude of tasks, from planning training exercises to landscaping, to accepting new recruits. His formal office was located in the Administration building, but work would often follow him home, where he would host meetings in his study. Just like kids today, Isabel and other officers' children would attend school, play with toys and run around exploring the fort.

However, the duties of the commanding officer’s wife looked quite different from the duties of most parents today. Jessie Phisterer, like many other upper-class families in the early 1900s, had a maid that she employed to help run the house. Their maid took care of cooking, cleaning and childcare. She was also likely a seamstress for the family. This freed up Jessie to work on correspondence, embroidery, some childcare, planning dinners and other functions.

Life After the First World War

The arrival of World War I precipitated change for families at Fort Columbia in more than one way. Families of officers had to move elsewhere as the men stationed at the fort prepared for a war that never arrived on U.S. shores. With the advancements in naval and airpower technologies seen in the first world war and the 1920s, it was plainly obvious that the gun batteries at Fort Columbia were quickly becoming obsolete. This obsolescence was one reason all three forts on the Columbia River — Fort Columbia, Fort Canby (now Cape Disappointment State Park) and Fort Stevens in Oregon were placed on inactive status in 1930.

Inactive status did not mean these forts were abandoned. Two officers and 39 enlisted men were assigned as caretakers to maintain all three coastal forts. Life at an inactive fort was much quieter than life at an active one. The booms of artillery fire practice, brass band music from parties and shouting and laughter of men in the barracks, were replaced with the calling of eagles, waves hitting the shore and quiet conversation from the few members of a caretaker’s family living at Fort Columbia.

One such caretaker was Sergeant Mort Miles, who was assigned to the three forts from 1921-1938. During his time at Fort Columbia, he lived in the Commanding Officer’s quarters with his wife, Anna, and his children, Mort, Raymond and Lillian. Life for Mort and his family at Fort Columbia was very different from the life of Col. Phisterer and his family, even though they lived in the house only twelve years earlier.

For starters, Sgt. Miles did not have to undertake the same command responsibilities that Col. Phisterer did, rather his focus was on ensuring the upkeep of Fort Columbia. This included performing preventative maintenance, repairing buildings and taking care of the landscaping. He would also help direct work detail assignments of other men at Fort Columbia. Life inside the home was also different as the Miles family did not have a maid. Anna was responsible for childcare, cooking and cleaning. Life for their children, however, was much the same as it had been in the past, with their only responsibilities being school and figuring out just how much mischief they would get into.

Lillian recounted a story about how, one day, her brother and her noticed that there were monkeys wandering around Fort Columbia. The two of them gathered food, left it outside their house and spent the afternoon peering through the windows in the parlor, watching and waiting to see if the monkeys would take their snacks. Eventually, the monkeys took the bait and ran off with their prizes.

Lillian said she and her brother got great joy out of watching the monkeys eat and play. Despite how cool it would be to have monkeys at Fort Columbia, there are no monkeys there now. It is thought that the monkeys Lillian fed arrived on a ship that docked across the river in Astoria, Oregon. It's possible one of the soldiers stationed at Fort Columbia brought them back to the fort.

World War II and Beyond

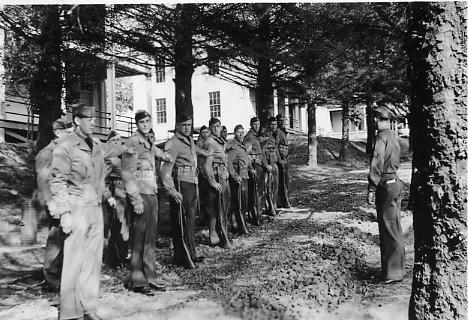

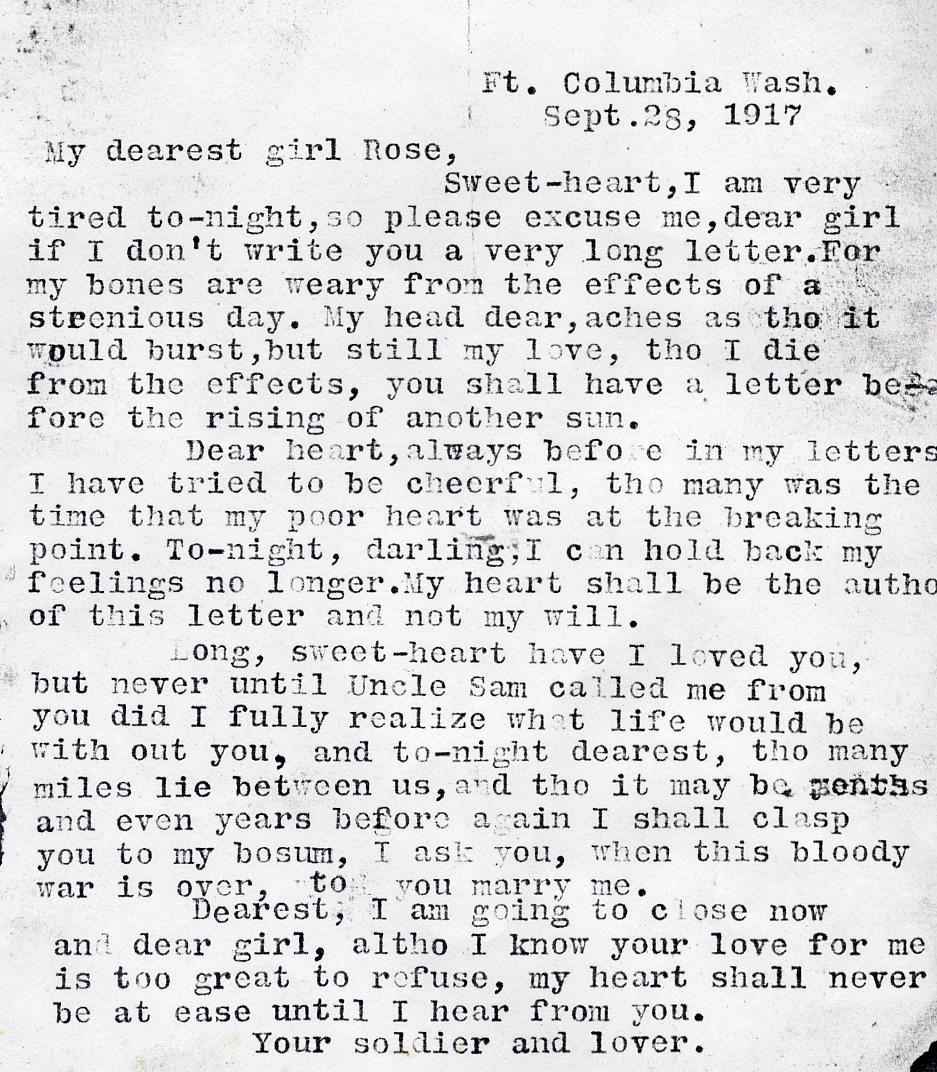

The onset of World War II brought more change to Fort Columbia as the population swelled from just a few soldiers to over 500 men. This was most it would ever see during its operation. Families were once again absent from the fort during this time, but soldiers regularly wrote letters home to loved ones. The booms of guns and mines firing and exploding was once again present on the river, replacing the quietude that had reigned over the fort for just over 20 years.

Nowadays, the only families wandering Scarborough Hill and the Commanding Officers' quarters are those who choose to visit Fort Columbia State Park. After World War II, Fort Columbia was scheduled for disposal. Luckily, it was saved from deterioration when the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission acquired the land in 1950 after local community members in Chinook advocated for fort’s preservation.

The buildings of Fort Columbia stand as a reminder of the past and allow visitors to peek into the daily lives of not only the soldiers stationed there, but also their families.

The Barracks building that hosted parties, poker nights and the sleeping quarters of enlisted men is now an Interpretive Center, and the Commanding Officers' Quarters is a house museum that harkens back to and tells the story of Col. Phisterer’s time at Fort Columbia. Even though the families and their responsibilities at Fort Columbia changed overtime, it remains a place full of fond memories for those who called it home.

Originally published April 17, 2025