Moran State Park History

A Mountain on an Island

The pinnacle of Moran State Park, Mount Constitution, rises 2,407 feet directly from sea level to the second highest point on an oceanic island in the contiguous 48 US states. The rocks that make up the heights of Mount Constitution began as lava erupting on the ocean floor or slowly accumulating sediments formed by skeletons of marine microorganisms, windblown dust and volcanic ash settling to the ocean floor. The pillow basalts, chert and shale seen at rocky exposures in the park are evidence of these events. These deep oceanic rocks were thrust up and out of the ocean and stacked on top of each other as tectonic plates collided with the ancient coast of Washington. More recently, ice age glaciers gouged and polished the bedrock.

Indigenous Lands

Moran State Park lies within the traditional territories of Coast Salish Indigenous people whose present-day descendants include members of the Lummi Nation, Samish Indian Nation, Suquamish Tribe, and Swinomish Indian Tribal Community. For thousands of years the rich waters of the San Juan Archipelago have provided habitat for a diverse community of life that forms the basis of their cultures. As winter days lengthen into spring, herring and herring roe collect in the eelgrass beds near shore. A little later, spring Chinook salmon pass through the island channels. Early summer brings sockeye salmon, harvested for millennia with reef nets. Sea urchins are gathered by expert divers in late summer, and clamming peaks in the fall.

Local tribes ceded ownership of the area to the US federal government under duress in the Treaty of Point Elliot in 1855, keeping rights to harvest natural resources in their usual and accustomed places, including the lands and waters of today’s Orcas Island. After government land surveys were completed in 1874, most of the land in today’s Moran State Park was conveyed into private ownership under the US land disposal laws.

Homesteads, Land Grants and Cash Sales

Four parcels of about 160 acres each were transferred as Homestead Entry patents under the Homestead Act of 1862, which provided title to the land after five years of continuous residence, building a home, farming and making improvements. All homesteaders who “proved up” on land in today’s Moran State Park sold their property within a few years of obtaining the patent.

Nearly 350 acres were granted to the Northern Pacific Railroad as part of the nearly 40 million acres the US Congress gave to the company to subsidize the construction of railroad lines into the western states (no railroad was ever built on Orcas Island). Some land was granted to the State of Washington at statehood to provide revenue for public schools.

The vast majority of the land now making up the park was transferred to private owners as Cash Entry patents, a form of land sale of the public domain lands. Some was purchased as speculative investments by people who came to the island as tourists.

Robert Moran

Orcas Island embraced the tourism industry earlier than many places. Excursion steamers brought tourists to the island from Seattle, Bellingham, and other points around Puget Sound by the late-1800s. Many visitors wanted to visit the summit of Mt. Constitution to take in the grand views, spurring development of a wagon road up the mountain.

The establishment of a State Park on Orcas Island is due to the generosity, foresight and determination of Robert Moran.

Arriving in Seattle in 1875 with only a dime in his pocket, Moran started his new life by negotiating credit for breakfast. Moran worked his way up and learned from mentors in the shipping business. In 1879, he was hired as chief engineer on the Cassiar for the steamer's Alaska run, where he stayed for three years. During this time, Moran became friends with naturalist John Muir, meeting him when he was a guest onboard the ship for a journey to study Southeast Alaska and Glacier Bay. Muir's approach to nature and spirituality fascinated Moran, and this contact with Muir is credited as the beginning of his interest in land preservation.

Moran went on to found and manage a major shipbuilding firm and was elected Mayor of Seattle in 1888. In 1906, he was diagnosed with cardiac disease, which he blamed on the stresses of his lifestyle. To regain his health, he retired, sold his company and moved to Orcas Island. With considerable wealth at his disposal, he began building an estate and acquiring land. Beginning with a sawmill on the shore of East Sound at the outlet of Cascade Lake, he eventually acquired property from the shore nearly to the summit of Mount Constitution. His purchases included three out of the four original homesteads, the Northern Pacific Land Grant lands and many of the holdings that began as Cash Entry patents. 560 acres of Cash Entry patents had been obtained by his relatives, including his brother John, sister Annie and three nieces.

Beginning in 1910, Moran offered to donate much of the land for park purposes if the state could purchase additional lands including the summit of Mount Constitution. Largely due to his lobbying, the Washington Legislature passed House Bill 509, signed by Governor Ernest Lister on March 19, 1913. The law established a State Board of Park Commissioners authorized to receive donations of lands for state park purposes. The law did not provide any funding for operation of the parks, so the Board was not willing to take on responsibility for the large acreage that Moran was offering.

On March 19, 1921, Governor Louis F. Hart approved House Bill 164, establishing the State Parks Committee with funding and enforcement authority to manage state parks. On April 21, 1921, the State Parks Committee formally accepted the donation of nearly 2,700 acres of land from Robert Moran to create Moran State Park. The park was dedicated on June 18, 1921, establishing Washington’s first state park with a large land base. Moran donated additional parcels in 1925 and 1926, and the State Parks Committee purchased or accepted donations from others, including 80 acres at the summit of Mount Constitution in 1927. An inholding, private land surrounded by park lands, of 320 acres including much of the Mount Constitution Road was acquired by court-approved condemnation in 1932, allowing work to proceed on $40,000 worth of “engineering, construction, betterment” of the road approved by the state legislature in 1931.

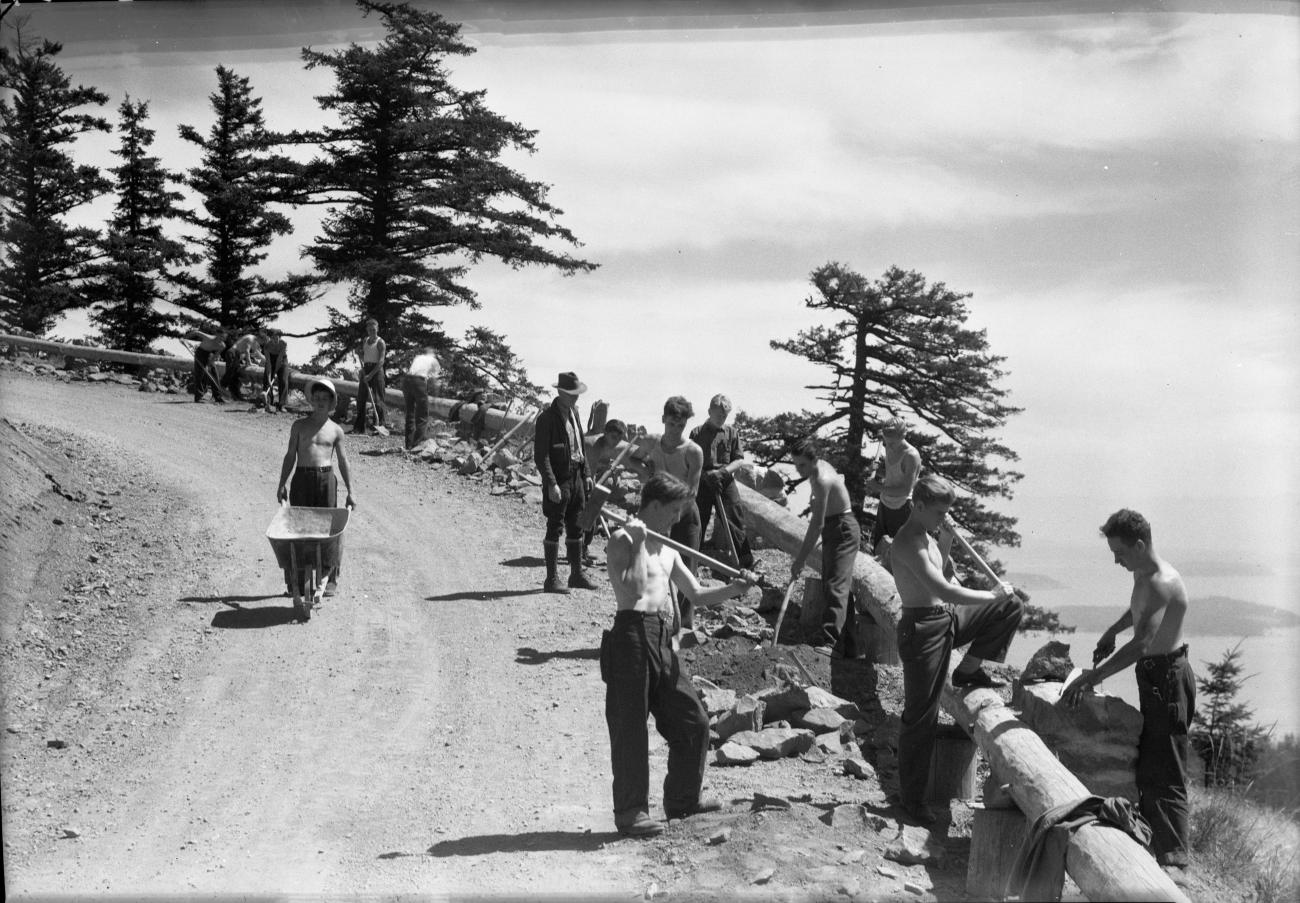

The Civilian Conservation Corps

In the 1930s as the Great Depression deepened, people throughout Washington and across the United States struggled with poverty as job losses and business closures erased their economic security. Newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved fast to provide material relief for suffering families, and one of the earliest hallmark programs of the administration was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Intended to provide useful employment and training for single men aged 18 to 25, the CCC ultimately provided jobs for more than 2 million enrollees who performed work in national and state parks and forests at more than 500 camps.

State Parks Superintendent William Weigle traveled to Washington D.C. in April of 1933 to attend meetings related to the establishment of the CCC. Weigle worked quickly and used his contacts in the Forest Service and other branches of the federal government. The camp at Moran State Park was authorized on May 26. Designated SP-1, Camp Moran was the first of 12 that were eventually established in Washington State Parks. On June 17, 1933, CCC Company 1233 arrived at Camp Moran near Cascade Lake, beginning a succession of 16 six-month enrollment periods, the longest continuous CCC program in any of Washington’s state parks. The complex at Camp Moran included five barracks, a mess hall, three education buildings, wash house, administration building and housing for the army and technical personnel overseeing logistics and construction projects.

CCC crews built caretaker residences, restrooms, picnic shelters, and kitchens. They built miles of trails and provided much-needed maintenance on the park’s roads. Their biggest project was the construction of the stone tower at the summit of Mount Constitution. All the materials used for its construction, even the water necessary to mix the mortar, was hauled over eight miles with an elevation climb of 2,000 feet.

Architect Ellsworth Storey was assigned to Camp Moran as a technical specialist in July of 1935. He had begun developing designs for the tower in the fall of 1934 and sent three studies to Robert Moran for his "reaction to each" in mid-October. The tower was constructed of reinforced concrete and sandstone. Each floor of the tower was built with a room in the southern half and stairs in the northern half, rising approximately 53 feet tall. The construction was significant in the State Parks CCC program for the Western Region, and was visited by Lawrence Merriam and Conrad Wirth, the Assistant Director of the National Park Service, multiple times as the work progressed. Wirth commented on the high quality of the park development, noting that the work was of a higher grade than any other place that he had seen.

Because the CCC stayed longer at Moran State Park than other parks and only limited additional development has occurred in the park since the CCC work, a visit to Moran allows one of the most immersive experiences of the Depression Era work available in any Washington state park.

By creating opportunity out of a national crisis, the CCC programs in Washington State provided lifelong benefits for enrollees and made lasting investments in state parks that visitors still enjoy today.

The State’s Finest Nature Spot

Robert Moran stayed involved in the park for the rest of his life and commented in his autobiography that “after the State's acceptance of the gift, I built miles of roads and trails, including bridges, arches, and other improvements at my own cost. This State playground is, in my judgment, the State's finest nature spot, to be enjoyed by posterity to the end of time.”

On June 18, 2021, Washington State Parks celebrated Moran State Park’s 100th birthday with the opening of the Summit Visitor Center on top of Mount Constitution.

Sharing the histories of Washington’s state parks is an ongoing project. Learn more here.