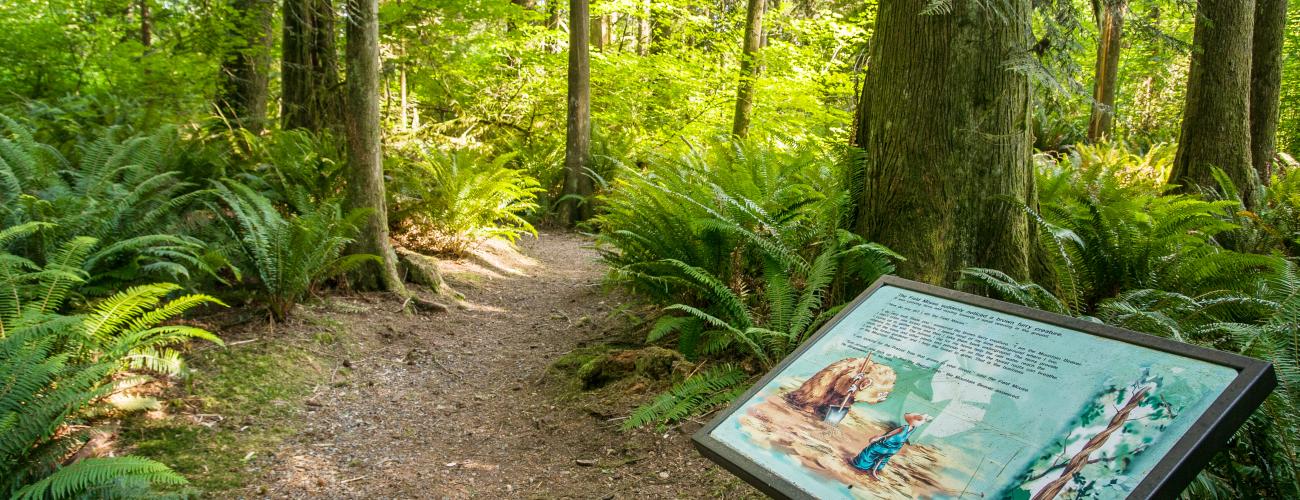

Squak Mountain State Park History

“To know the land, one must feel it out inch by inch with the feet.” –Harvey Manning

A generous land donation and the hard work of community activists has ensured that Squak Mountain State Park will be an enduring piece of wilderness close to the homes of millions of urban residents.

The bedrock of Squak Mountain is made up of rocks that formed from sediments carried by rivers into an ancient coastal estuary, where their increasing weight caused the land to sink, only to be buried by even more sediments. In time, the sedimentary layers accumulated more than one mile of thickness. As the sediments slowly collected, sub-tropical forests flourished on the landscape. Trees died and were buried before they began to decay, slowly converting into peat. Further burial and heat, possibly from regional molten magma intrusions in the Cascade Mountains, reduced the water, methane and carbon dioxide in the peat, and changed it into coal. The coal seams are found today in a layer of sedimentary rocks that geologists have named the Renton Formation.

Tectonic action that continues to the present has wrenched the layered rocks into an uplifted arch that geologists call an anticline, which forms the string of foothill peaks now known as Tiger Mountain, Squak Mountain and Cougar Mountain.

Indigenous Land

Squak Mountain State Park lies within the traditional territory of Coast Salish Indigenous people whose present-day descendants include members of the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, and Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. For thousands of years the foothills of the Cascade Mountains and the rivers that flow through them have provided habitat for a diverse community of life that forms the basis of their cultures.

Local tribes ceded ownership of the area to the US federal government under duress in the Treaty of Medicine Creek in 1854 and the Treaty of Point Elliot in 1855, keeping rights to harvest natural resources in their usual and accustomed places, including the rivers and lakes of the Cascade foothills.

Government surveys were completed in 1873, and the land in the north part of today’s Squak Mountain State Park passed into private ownership from 1889-1892 as Homestead Entry patents to people that “proved up” their land claims by constructing a dwelling and residing on the property.

One full square mile surveyed section making up most of the southern half of today’s Squak Mountain State Park was granted to the Northern Pacific Railway in 1895 as part of a grant of nearly 40 million acres to the company approved by the US Congress in 1864 to subsidize construction of railroad lines into the western states. The land was sold to other private owners to provide additional profit to the company.

Additional lands at the eastern and southernmost extent of today’s park were granted to the State of Washington at statehood. The grant was a portion of the millions of acres of public domain lands given to the state to manage as trust lands “for all the people” to financially support public institutions.

What’s in a Name

Squak Mountain takes its name from the creek valley on its east side, which in turn was derived from the Indigenous word “squak” which is variously translated as an imitation of bird sounds and a placename identifier for the creek known today as Issaquah Creek.

King Coal

The coal seams in the Renton Formation at Squak Mountain were identified as a possible source of commercially viable coal as early as 1859, but large-scale operations didn’t begin until rail transportation reached the area in 1887. The Issaquah & Superior Mine tunneled into the northern slope of Squak Mountain in 1912. The Richmond-Harris Mine was located at the northwest corner of today’s Squak Mountain State Park. Coal mines were the primary employer in the city of Issaquah (which also took its name from the Indigenous placename) at the beginning of the 20th century, with laborers ranging in age from 14 to over 70. Most coal mines closed in the 1920s due to a drop in demand as coal was replaced with other fossil fuels for home heating and industrial uses.

Timber was harvested from the slopes of Squak Mountain, and the construction of Interstate 90 in the 1960s ushered in the era of rapid suburban housing construction in the Issaquah area.

The Bullitt Family Cabin

Beginning in the 1940s, Stimson Bullitt, an heir to a prominent Pacific Northwest family’s fortune made in timber, real estate and broadcasting, began buying small parcels of logged land on Squak Mountain. In 1952, he built a two-room family vacation cabin on his property which included over 600 acres surrounding the mountain's 2,024-foot summit. In the early 1970s, the family trust deeded the cabin and property to three of Bullitt’s children (Ashley Ann Bullitt, Scott Bullitt and Jill Hamilton Bullitt). Purportedly, Stimson Bullitt suggested that they could use the property to build homes for themselves, subdivide and develop the property for suburban housing, or give the property as a public park.

Making a Park

On June 17, 1972, the three Bullitt children donated 590 acres on Squak Mountain to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (WSPRC) for use “as a wilderness park… the wilderness character of which shall include the absence of any vehicular use, whether powered or not, the absence of horses, the absence of any roads other than footpaths, and the absence of any man-made structures.”

In spite of the fact that the donated land did not include a point of access from a public road on which parking facilities and trail access could be constructed, local trail users began to visit. Sadly, repeated vandalism destroyed all of the former Bullitt cabin except its large stone fireplace, which remains as a trailside destination.

On July 17, 1984, the WSPRC purchased a 23-acre parcel from the North American Refractories Company, a portion of the former Richmond-Harris Coal Mine property, to provide trailhead parking and trail access to the park.

The Issaquah Alps

Local community leaders recognized the recreational potential of the three summits (Tiger, Squak and Cougar) that formed the backdrop of their neighborhoods. In 1979, local author and wilderness preservation activist Harvey Manning quit smoking and was advised by his doctor to “walk his addiction away” by hiking 1,000 miles in six months. Unable to visit the snow-covered peaks of his favored North Cascades National Park and Alpine Lakes Wilderness during the winter months, he turned instead to the nearby foothills.

Finding that the area possessed hidden natural gems and historic sites and much potential for peaceful year-round foot travel, but also that it faced pressures from suburban development, he joined with others to work for the protection of the land for recreation and conservation. He coined the term “Issaquah Alps” to brand the lobbying effort and was a founding member and first president of the Issaquah Alps Trail Club to further the mission. Manning called the Bullitt’s donation of Squak Mountain to the WSPRC “the greatest act of environmental benevolence in local history” and built on that beginning to build an interlaced system of protected lands.

Bill Longwell was an equally avid hiker of the Issaquah Alps, as well as a high school history and literature teacher, musician and athlete. Dubbed “Chief Ranger” of the Issaquah Alps by Harvey Manning, Longwell volunteered to survey, lay out and lead trail building efforts at Squak Mountain and elsewhere.

In March 1992, the non-profit Trust for Public Land (TPL) reached an agreement with the Grand Ridge Partnership, a development company, to suspend a major new housing development adjacent to the lands donated by the Bullitt family on Squak Mountain. TPL purchased 17 building lots and obtained an option to purchase another 14 lots. TPL held the lots for resale to the WSPRC when funds for the purchase had been appropriated by the state legislature. The transaction was completed on September 18, 1995, with WSPRC taking ownership of all of the additional property.

In 1989, the Washington State Legislature authorized the Trust Land Transfer Program. The legislature funds the transfer of state trust lands with special ecological or social values and have low income potential out of state trust ownership to a public agency that can manage the property for those values. Money from the transfer provides revenue for the trust beneficiaries and is used to buy productive replacement properties that will generate future trust income.

364 acres were added to Squak Mountain State Park through the Trust Land Transfer Program in 1993 -1994, protecting forested habitat areas on the southern and eastern edges of the park as well as the location for the main park trailhead.

The core of the park remains the original 590-acre donation, still managed as a wilderness park with access only on foot, slowly and deliberately.

Sharing the histories of Washington’s state parks is an ongoing project. Learn more here.